Primary biodiversity data

| In this section, you will learn how GBIF makes primary biodiversity data accessible, the accepted dataset types and how GBIF uses the taxonomic backbone to provide taxonomic information. |

When we refer to primary biodiversity data, we mean the data that document where and when species have been recorded. This knowledge derives from many sources, including everything from museum specimens collected in the 18th and 19th century to geotagged smartphone photos shared by amateur naturalists in recent days and weeks.

The GBIF network draws all these sources together through the use of data standards, such as Darwin Core, which forms the basis for the bulk of GBIF.org’s index of hundreds of millions of species occurrence records. Publishers provide open access to their datasets using machine-readable Creative Commons licence designations, allowing scientists, researchers and others to apply the data in hundreds of peer-reviewed publications and policy papers each year. Many of these analyses—which cover topics from the impacts of climate change and the spread of invasive and alien pests to priorities for conservation and protected areas, food security and human health— would not be possible without this.

GBIF dataset classes

We encourage data holders to publish the richest data possible to ensure their use across a wider range of research approaches and questions, but not every dataset includes information at the same level of detail. Sharing what is available through GBIF.org is valuable, because even partial information answers some important questions.

The four classes of datasets supported by GBIF start simply and become progressively richer, more structured and more complex.

-

Meta-data only - datasets describing undigitized resources like those in natural history and other collections

-

Checklist - a catalogue or list of named organisms, or taxa

-

Occurrence - the evidence of the occurrence of a species (or other taxon) at a particular place on a specified date. Occurrence datasets make up the core of data published through GBIF.org

-

Sampling-event - offering evidence that a species occurred at a given location and date, but also making it possible to assess community composition for broader taxonomic groups or even the abundance of species at multiple times and places.

More information on dataset classes can be found on the GBIF website.

You might also want to explore how to choose a dataset type.

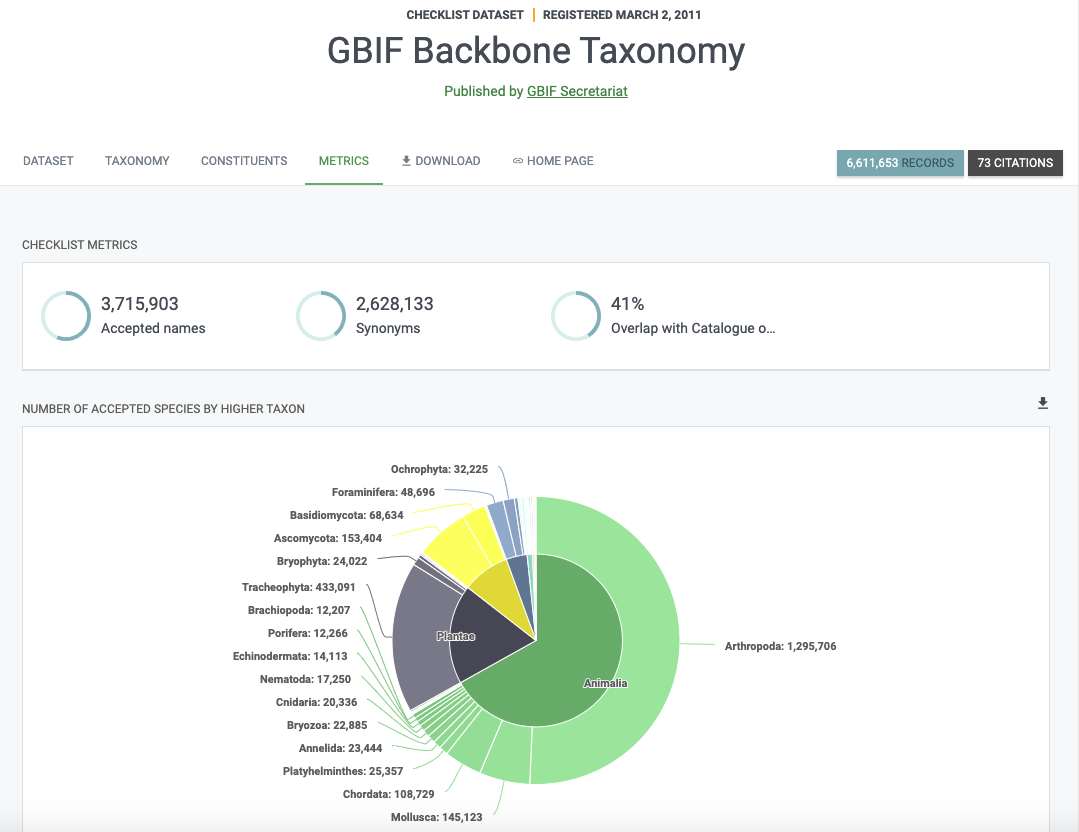

GBIF taxonomic backbone

What is the GBIF Backbone taxonomy?

The Backbone taxonomy is actually a GBIF dataset. But not just any dataset, it is probably the most important dataset for GBIF. On its page, it is defined as:

a single synthetic management classification with the goal of covering all names GBIF is dealing with

Why does GBIF need a backbone?

The backbone is needed to organize the data available on GBIF. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to do any taxonomic search and it would be difficult to generate consistent statistics and maps.

As you can imagine, not everyone uses the same classifications or names. This results in considerable variations in higher taxa and a large number of synonyms. The backbone aims to bring all these names together and organize them.

How is the backbone generated?

The backbone is built from other checklists. These include:

-

55 authority checklists,

-

a checklist generated from the type specimens shared on GBIF,

-

two large sources for stable Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): iBOL Barcode Index Numbers and the UNITE Species Hypothesis identifiers,

-

and any checklist shared by PLAZI.org on GBIF (currently 27,054 but not all these were available when the backbone was generated).

These checklists are ordered by priority starting with the Catalogue of Life for most taxa. This order is crucial as it shapes the taxonomy.

| Note that many sequence-based occurrences have no Latin names but are named using species hypotheses (UNITE: fungi) or Barcode Index Numbers (iBOL: primarily animals). This is why adding these two major sources of stable OTUs to the latest backbone taxonomy significantly improves GBIF’s indexing functionality for sequence-based biodiversity data. |

The information above is an excerpt from a 2019 blog post by Marie Grosjean. Read the blog post for more detail on the backbone.