Principles of GBIF-mediated data

| In this section, you will learn about the principles that GBIF follows with regards to data and how data in the GBIF portal are FAIR. |

Digital object identifiers

A Digital Object Identifier, or DOI, is a standard, permanent identifier that provides an actionable, interoperable, persistent link to any entity. The concept is that DOI differs from commonly used references like URL web links because it identifies an object itself as a first-class entity, not simply the place where the object is currently located.

In the context of GBIF.org, DOIs serve as stable identifiers for four different types of things:

-

datasets from the GBIF network

-

data downloads from GBIF.org

-

research articles and reports published by scientific journals, agencies and NGOs

-

materials deposited in a general-use repository

GBIF assigns DOIs to all datasets and occurrence downloads. When data is used, following DOI citation practice ensures an easy and consistent way of crediting dataset holders while also allowing for reproducibility. The DOIs will always resolve to dataset or download pages, even if the underlying data is no longer available.

GBIF started issuing DOIs on 3 February 2015. Downloads requested before this date do not have DOIs, however, if you wish to cite older downloads, you can contact helpdesk@gbif.org and we will assign DOIs as appropriate.

Standards

The data available through GBIF.org and its associated services is the result of the GBIF network of Participants and publishers applying shared rules and conventions to describe, record and structure thousands of different datasets drawn from hundreds of institutions around the world. Common standards are the main enabler for bringing together the hundreds of millions of primary biodiversity records in the GBIF index.

Within the biodiversity domain, the group most often responsible for developing and maintaining data standards is Biodiversity Information Standards. This nonprofit scientific and educational association focuses on the development of standards for the exchange of biological and biodiversity data. Members of the biodiversity community generally refer to this group as TDWG (pronounced tad-wig)—a vestigial reminder of its earlier manifestation as the Taxonomic Databases Working Group.

Commonly use standards include:

-

Darwin Core: The Darwin Core Standard (DwC) offers a stable, straightforward and flexible framework for compiling biodiversity data from varied and variable sources. The majority of the datasets shared through GBIF.org are published using the Darwin Core Archive format (DwC-A).

-

Ecological Metadata Language (EML): Ecological Metadata Language is a metadata standard that records information about ecological datasets in a series of modular and extensible XML document types. All of the descriptions of datasets in GBIF.org rely on ‘metadata’—that is, the information about data—using the open-source EML standard, which is administered and maintained by The Knowledge Network for Biocomplexity. Each Darwin Core Archive includes as one of its components an EML file (written in XML format).

-

BioCASe/ABCD: The Biological Collection Access Service, commonly referred to as BioCASe, is an international network linking biological collections data from natural history museums, botanical/zoological gardens and research institutions. The BioCASe protocol relies on the Access to Biological Collections Data (ABCD) data exchange standard, which TDWG also administers.

Open data

In keeping with a 2014 decision by the GBIF governing board, data publishers must assign one of the three Creative Commons options to any occurrence dataset. The Governing Board recognized the need for much greater clarity both for data publishers and users on how data may be used when shared via GBIF.org. Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that helps overcome legal obstacles to the sharing of knowledge and creativity to address the world’s pressing challenges.

| Note that the CC-BY-NC licence has a significant effect on the reusability of data. GBIF encourages data publishers to choose the most open option they can wherever possible. It is important to note that images are not subject to the same licence that is applied to the dataset and may have more restricted terms of use. Lastly, attribution/citation is a community norm, so even if the publishers has waived conditions for use, attribution is expected. |

FAIR data

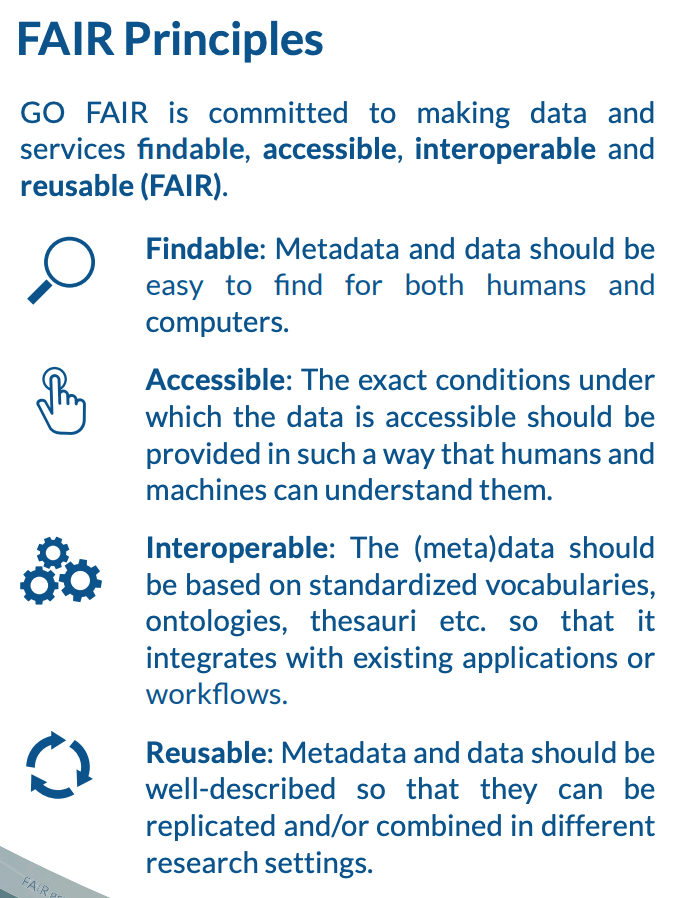

Many articles from 2011-2016 documented a crisis in scientific reproducibility (see below). In 2016, the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship were published in Scientific Data. The principles were designed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, the Interoperability and the Reusability of datasets and address "an urgent need to improve the infrastructure supporting the reuse of scholarly data." Implementation of these principles began in 2018. You can read more about How to GO FAIR on GO-FAIR.org.

Data found on GBIF.org are FAIR.

Literature references

Baker (2016) 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 533: 452-454 (26 May 2016) doi:10.1038/533452a

Baker (2016) Reproducibility: Seek out stronger science. Nature 537: 703-704 (29 September 2016) doi:10.1038/nj7622-703a

Nature editorial (2016) Reality check on reproducibility. Nature 533: 437 (26 May 2016) doi:10.1038/533437a

Baker (2016) Statisticians issue warning over misuse of P values. Nature 531: 151 (10 March 2016) doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19503

Nosek et al. (2015) Promoting an open research culture. Science 348(6242): 1422-1425. DOI:10.1126/science.aab2374

Leek and Peng (2015) Statistics: P values are just the tip of the iceberg. Nature 520: 612 (30 April 2015) doi:10.1038/520612°

Nuzzo (2015) How scientists fool themselves – and how they can stop. Nature 526: 182–185 (08 October 2015) doi:10.1038/526182a

Hayden (2013) Weak statistical standards implicated in scientific irreproducibility. Nature doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14131

Young (2012) Replication studies: Bad copy. Nature 485, 298–300 (17 May 2012) doi:10.1038/485298a

Callaway (2011) Reports finds massive fraud at Dutch universities. Nature 479, 15 (1 November 2011) doi:10.1038/479015a